More Information

Submitted: October 01, 2021 | Approved: November 09, 2021 | Published: November 11, 2021

How to cite this article: Naik GT. Ocular manifestations in a case of progeroid syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021; 5: 025-028.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijceo.1001040

Copyright Licence: © 2021 Naik GT. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Progeria; Progeroid syndrome; Ocular manifestations

Ocular manifestations in a case of progeroid syndrome

Gajaraj T Naik*

Karwar Institute of Medical Sciences, Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, India

*Address for Correspondence: Gajaraj T Naik, Karwar Institute of Medical Sciences, Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, India, Email: [email protected]

Progeria syndromes are very rare genetic diseases characterized by premature aging changes. There are several phenotypes and variables noted in literature in some cases difficult to specifically classify a specific syndrome. It occurs due to mutation in DNA repair genes. The most common ocular findings are loss of eyebrow and eyelashes, brow ptosis, lid margin changes, entropion, Meibomian gland dysfunction, severe dry eye, corneal opacity, cataract, poor mydriasis, and rod-cone dystrophy. We report this case with all the above ocular manifestations in 19year old teenager with additional finding being retinal detachment.

Progeroid syndromes are a cluster of genetic disorders characterized by various clinical features and phenotypes of physiological aging prematurely, some of which are even fatal. Ataxia-telangiectasia, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, Cockayne syndrome, Hutchinson-Gilford syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, xerodermapigmentosum, and Werner syndrome are among some of progeria syndromes [1]. The derivation of the word progeria means ‘prematurely old’ in greek. It is caused by de novo dominant mutation in the LMNA gene (gene map locus 1q21.2) and characterized by growth retardation and accelerated degenerative changes of the skin, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems [2].

Classical Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome is usually caused by a sporadic autosomal dominant mutation 6. There are a few atypical forms of progeria, also called non-classical progeria in which growth is less retarded, scalp hair fall off slowly, a progression of lipodystrophy is delayed, osteolysis is more visible with an exception in face and survival is observed mostly till adulthood [3].

Ocular manifestations in progeria syndrome i.e in classical variant are loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, poliosis, lagophthalmos, narrowing of the palpebral fissure, superior sulcus deformity, lid retraction, upper lid lag in downgaze, poor pupillary dilatation, cataract, etc..., [2].

In non-classical variant depending upon gene mutation and penetrance level ocular manifestations can range from lid abnormalities, dry eye, corneal opacity, poor mydriasis, cataract, pigmentary retinopathy, rod and cone dystrophy, optic atrophy etc..., [4].

In this study, we report 19 year old teenager with the non-classical progeroid syndrome and ocular manifestations associated with it. Consent was taken to examine and ethical clearance cleared from Department Head.

A 19-year-old teenager came to our OPD in Karwar Institute of Medical Sciences Karwar with complaints of diminution of vision right eye for 5 years gradually progressive aggravated during the last 6 months. The patient also complained of recurrent redness, watering, foreign body sensation, severe photophobia, and intolerance to sunlight for 5 years. The patient has a history of poor vision during school age and thus discontinued schooling at the 6th standard. The patient doesn’t work for a living and stays inside the house regularly. The Patient also has loss of scalp hair, eyebrows, skin wrinkling and pigmentation, dental caries since 5 years.

According to parents, he was the first child of family, other 3 being younger sisters who are asymptomatic. Parents had non-consanguineous marriage. His antenatal, natal, and postnatal history were uneventful. He didn’t have significant health problems until the 6th standard. Parents had earlier consulted many doctors but treatment history was not available. The patient had a history of seizures during childhood but no diagnosis of epilepsy was made. No history of hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia was diagnosed.

He was poorly built & nourished, and was conscious & oriented to time, place& person. His IQ was adequate. His height was 155 cm and weight 45 kg which was statistically less than average at this age indicating cachectic dwarfism. His head circumference was 54 cm. The skin was pale and aging signs like wrinkling and pigmentation were present. The face had hypopigmented spots in the malar area. There was generalized hair loss, loss of subcutaneous fat. The Musculoskeletal system showed osteoporosis changes in the X-ray. Cardiac and respiratory systems were normal. Neurological examination showed decreased muscle power grade 3-4 with brisk reflexes. There was a mild sensorineural hearing loss which was confirmed by the audiogram. All the signs pointed out to aging changes.

Extra Ocular manifestations noted were loss of eyebrow and eyelashes with few remaining which had poliosis. Excessive wrinkling of the forehead was noted. Inner canthal distance 40 mm, outer canthal distance 110 mm, inter-pupillary distance 76 mm, vertical palpebral fissure 10 mm, horizontal palpebral fissure 18 mm. There was no proptosis. Head posture, ocular posture, and extraocular movements were normal.

Lid changes included lid margin abnormalities, meibomian gland dysfunction, loss of eyelashes, mild grade 1 entropian, and no adequate tarsal support. Cyst of Zeiss was noted in the left lower eyelid. Conjunctiva dryness noted, Schirmer’s testreading was less than 3 mm indicating severe dry eye. Cornea had dry lusterless look, both eyes had inferior corneal opacity right more than left with 360 degree superficial vascularization in right cornea and 30 degrees in left cornea. Deep vascularization of 2 O’ clock hours was noted at 7 O’ clock position. Corneal opacity in right eye was involving pupillary area. Senilearcus changes were difficult to look up as cornea was vascularized. On staining punctuate corneal erosions noted. Corneal sensation was decreased. Anterior chamber was normal in depth. Iris was normal. Pupil was round, reacting to light, but RAPD grade 1 was noted in right eye. IOP was measured by tonopen and was normal and gonioscopy was unremarkable. Patient could perceive light in right eye, but had inaccurateprojection of rays. He could count fingers at half meter with his left eye. Colour vision and contrast sensitivity could not be tested because of poor vision. Dry refraction revealed no glow in right eye and dull glow in left eye.

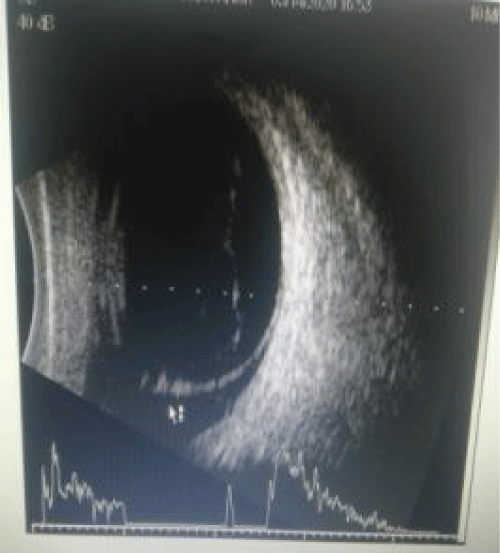

Slit lamp examination after dilatation with tropicamide 0.8% and phenylephrine 5% revealed poor mydriasis. Right eye showed brown cataract and left eye showed grade 3 nuclear cataract. The Fundus could not be visualized the right due to corneal opacity and cataract. Ultrasound Bscan of right eye showed inferior RD. Left eye fundus revealed normal optic disc and dull foveal reflex with normal peripheral retina. OCT showed altered foveal contour, NSD noted completely temporal to disc, hyperreflective areas above RPE, and CMT being 357 microns. The cause of poor vision in left eye was unexplained but clinically rod-cone dystrophy was kept in mind as the probable diagnosis.

After complete ocular evaluation patient was referred to physician for complete diagnosis. Provisional diagnosis of non-classical variable penetrance Cockayne syndrome, a form of progeroid syndrome was made. But genetic testing was not done to confirm Cockayne syndrome. Hence based on the clinical feature it was difficult to diagnose exact subtype of progeria syndrome. Cockayne Syndrome Type 3, a milder form; and xeroderma pigmentosa-Cockayne syndrome (XP-CS) can be more likely in this case (Images 1-4).

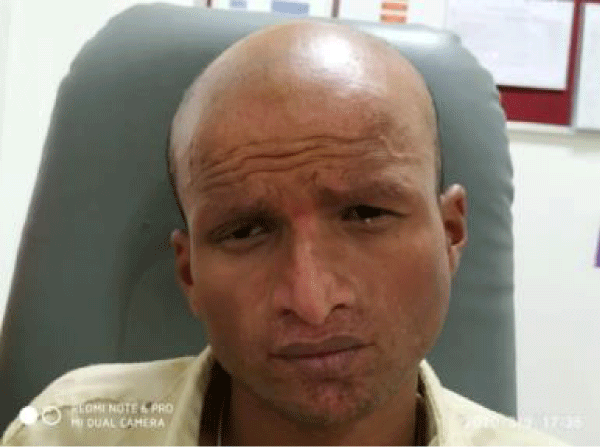

Image 1: Image 1: Showing progeria manifestations in this case. Alopecia, increased forehead wrinkles, skin wrinkling, poikiloderma at malar area, beaked nose.

Image 2: Showing loss of eyebrow eyelashes and poliosis. Entropian. Cyst of Zeiss, brow ptosis.

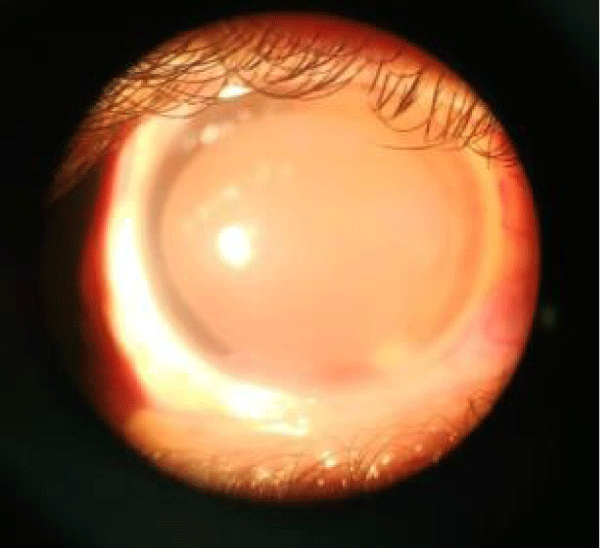

Image 3: Showing inferior corneal opacity with corneal vascularisation with grade3 nuclear cataract.

Image 4: Ultrasound Bscan right eye shows high spike membranous opacity indicating inferior RD.

Progeroid syndromes are extremely rare, fatal, genetic disorder of childhood with striking features resembling premature aging 5. 97% of reported cases are the Caucasians [6]. The classical progeria syndrome has a slight male predilection; the male-to-female ratio is 1.5:1.7

Currently, more than 142 patients with classical progeria syndrome i.e Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome. have been reported worldwide [3]. The incidence of Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome has been estimated at 1 in 4-8 million live births [6]. Based on prevalence and population data, the PRF estimates there should be around 66 instances of the disease within India [8].

Children with progeria usually have a normal physical appearance in early infancy. At approximately one to two years of age, affected children develop severe growth retardation, resulting in short stature, low weight, and delayed anterior fontanel closure. Other manifestations include abnormal facial appearance, micrognathia, dental carries, beak shape nose, and alopecia. Systemic manifestations include atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, congestive heart disease, hemiparesis, joint stiffness and dislocations, prominent scalp veins, loss of subcutaneous fat, skeletal defects, and other abnormalities [6,7].

Other features are prominent eyes, loss eyelashes and eyebrows, lagophthalmos, ectropion, ptosis, dry-eye syndrome, dry cornea, keratopathy, iridocorneal adhesions, corneal opacities, corneal clouding, cataract, strabismus, nystagmoid movements, refractive error, retinal vascular changes, retinal dystrophy, pigmentary retinopathy, and optic atrophy [4,9-11]. Many of these findings are based on individual case reports and are absent in the present case. Findings common in our case are loss of eyebrow and eyelashes, entropion, severe dry eye, corneal opacity and vascularization, cataract, poor mydriasis, and retinal dystrophy. Inferior Retinal Detachment in right eye was a new finding which was not seen in reported progeria cases in the past.

The ophthalmic anthropometric measurements such as horizontal palpebral fissure length, interpupillary distance, inner canthal distance, outer canthal distance in our patients are equal to aged-matched normal Indian values. Poor pupillary dilatation may be due to ischemic changes in the iris muscles secondary to microvascular insufficiency induced by atherosclerosis, however, visible atrophic changes were absent on slit-lamp examination in our patient [12]. Lipodystrophy of the orbital fat resulted in superior sulcus deformity. The progeroid syndrome should be classified as classical progeroid syndrome I,e Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome and non classicalvarients such as Werner’s syndrome (adult progeria), Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch syndrome (neonatal progeria), Hallermann-Streiff syndrome, mandibuloacral dysplasia, Cockayne’s syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, metageria and acrogeria [13].

We performed a Medline search with the keywords “Progeria”, “Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome”, “Ocular manifestations/signs/features/findings”, “Ophthalmic manifestations/signs/features/findings”, “eye”, “Premature ageing syndrome” and various combinations thereof (Table 1). All cross-references in citing literature were included in our search and referenced. Based on ocular manifestations in recorded progeria cases a table was put forth and ocular and systemic manifestations compared with our case. As per the table, our case cannot be specifically classified as any of the progeria syndromes. To the best of our knowledge Retinal Detachment has not been reported previously in the progeria syndrome.

| Table 1: Showing ocular and systemic manifestations recorded in progeroid syndrome and comparing with our reported case [2,14,15]. | |||||

| Clinical features | Classical progeria | Cockayne syndrome type 3 | Xeroderma pigmentosa | XP-CS | Our case |

| Loss of eyebrow eyelashes | +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ |

| Ptosis | +/- | - | - | - | - |

| Entropian | +/- | +/- | - | - | + |

| Corneal opacity | - | + | + | + | |

| Dry eyes | +/- | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| cataract | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Poor mydriasis | + | + | _ | _ | + |

| Retinal dystrophy | + | + | + | + | + |

| Optic atrophy | + | + | + | - | _ |

| RD | - | - | - | - | + |

| dwarfism | + | +++ | - | +/- | - |

| Skin photosensitivity | +/- | + | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Classical progeria face | ++ | +/- | - | - | - |

Life expectation in case of progeroid cases based on many studies is about 13 years. Myocardial infarction, secondary to atherosclerosis is the most common cause of death [6]. Still no treatment or prophylaxis has been discovered.

Drawback

Genetic work up was not possible as patient refused to go to higher centers.

We would like to thank the family of the patient for their cooperation and for consenting to the publication of the photographs.

- Kamenisch Y, Berneburg M. Progeroid syndromes and UV-induced oxidative DNA damage. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2009; 14: 8-14. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19675546/

- Chandravanshi SL, Rawat AK, Dwivedi PC, Choudhary P. Ocular manifestations in the Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011; 59: 509-512. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22011502/

- Hennekam RC. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: review of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2006; 140: 2603–2624. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16838330/

- Traboulsi EI, De Becker I, Maumenee IH. Ocular manifestations in cockayne syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol.1992; 114: 579-583. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1443019/

- Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003; 423: 293-298. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12714972/

- Stables GI, Morley WN. Hutchinson-Gilford syndrome. J R Soc Med. 1994; 87: 243-244. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1294455/

- Sarkar PK, Shinton RA. Hutchinson-Guilford progeria syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2001; 77: 312-317. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11320273/

- https://www.healthissuesindia.com/2018/05/27/progeria-awareness-in-india/

- Bhakoo ON, Garg SK, Sehgal VN. Progeria with unusual ocular manifestations: Report of a case with a review of the literature. Indian Pediatr. 1965; 2: 164-169. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5825824/

- Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S, Sachdev V, Smith AC, et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358: 592-604. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18256394/

- Iordãnescu C, Denislam D, Avram E, Chiru A, Busuioc M, et al. Ocular manifestations in progeria. Oftalmologia. 1995; 39: 56-57. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3214428/

- Gordon LB, McCarten KM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Machan JT, Campbell SE, et al. Disease progression in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: Impact on growth and development. Pediatrics. 2007; 120: 824-833. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17908770/

- Huang S, Lee L, Hanson NB, Lenaerts C, Hoehn H, et al. The spectrum of WRN mutations in Werner syndrome patients. Hum Mutat. 2006; 27: 558-567. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16673358/

- Natale V, Raquer H. Xeroderma pigmentosum-cockayne syndrome complex. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; 12: 65. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28376890/

- Ramkumar HL, Brooks BP, Cao X, Tamura D, Digiovanna JJ, et al. Ophthalmic Manifestations and Histopathology of Xeroderma pigmentosum: two clinicopathological cases and a review of the literature. 2011; 56: 348-361. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21684361/