More Information

Submitted: December 02, 2025 | Accepted: December 08, 2025 | Published: December 09, 2025

Citation: Legler K, Wakili P, Englisch CN, Rickmann A, Szurman P, et al. Side-Port Incision Patency and Influencing Factors in Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery. Int J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025; 9(2): 020-025. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ijceo.1001063.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijceo.1001063

Copyright Licence: © 2025 Legler K, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery; Side-port incisions; Patency; Limbus detection; Arcus seniles

Side-Port Incision Patency and Influencing Factors in Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery

Kira Legler1# , Philip Wakili1#

, Philip Wakili1# , Colya N Englisch1,2

, Colya N Englisch1,2 , Annekatrin Rickmann1,3

, Annekatrin Rickmann1,3 , Peter Szurman1,3,4

, Peter Szurman1,3,4 , Berthold Seitz5

, Berthold Seitz5 , Anna Theresa Frohlich1

, Anna Theresa Frohlich1 , Lisa Julia Muller1

, Lisa Julia Muller1 , Clemens N Rudolph1

, Clemens N Rudolph1 and Karl T Boden1,3*

and Karl T Boden1,3*

1Eye Clinic Sulzbach, Knappschaft Hospitals Saar, 66280 Sulzbach, Germany

2Department of Experimental Ophthalmology, Saarland University, 66421 Homburg/Saar, Germany

3Klaus Heimann Eye Research Institute, Knappschaft Hospitals, 66280 Sulzbach, Germany

4Centre for Ophthalmology, University Eye Hospital Tübingen, 72076 Tübingen, Germany

5Department of Ophthalmology, Saarland University Medical Center, 66421 Homburg/Saar, Germany

#These authors contributed equally to this work

*Address for Correspondence: Karl T Boden, MD, Eye Clinic Sulzbach, Knappschaft Hospitals, 66280 Sulzbach, Germany, Email: Karl.Boden@Knappschaft-Kliniken

Purpose: To analyze the patency rate of side-port incisions in femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery (FLACS) and to assess the impact of limbus detection quality, arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels extent on incision patency in a prospective clinical unmasked single-centre study.

Methods: A total of 159 eyes from 123 patients undergoing FLACS with the FEMTO LDV Z8 laser were included. Side-port incision patency, limbus detection quality, arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels extent were evaluated per corneal quadrant using a standardized protocol.

Results: A total of 130 eyes and 259 paracenteses were submitted to analysis. Notably, side-port incision patency was achieved in 99.2% of cases, of which 2.7% showed bridges. In only 0.8% a blade was necessary to open the incisions. Quality of limbus detection, arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels did not significantly affect the patency rate (p > 0.05).

Conclusion: FLACS using the FEMTO LDV Z8 achieves exceptional side-port incision patency, establishing its reliability as an automated alternative to manual incisions.

Femtosecond laser application has widely improved anterior segment surgery [1]. Nowadays, the computer-guided femtosecond laser, which is linked to an optical imaging system, has four main functions in FLACS, which include the capsulotomy, the creation of clear corneal incisions (CCIs), the treatment of keratometric astigmatism with arcuate incisions, and lens softening owing to fragmentation [2-4]. CCI includes the main incision and the side-port incisions, also referred to as paracenteses. Many studies have demonstrated a high precision and reproducibility of CCIs in FLACS [5-7]. At the same time, CCIs in FLACS are less prone to wound gape and leakage in comparison to those from conventional cataract surgery [4,8,9]. Ultimately, CCIs and particularly paracentesis patency become a critical topic. Among cataract surgeons working with FLACS, paracenteses are often considered challenging regarding their patency [10]. The first automated paracenteses were of poorer quality, as they were performed with high-energy lasers. Adjusting energy settings and using low-energy lasers such as the FEMTO LDV Z8 laser was a crucial advancement. However, from the surgeon’s perspective, paracenteses remain critical, which is due to their small size, which can make them difficult to find, and even the slightest bridges or adhesions can cause complete closure. In contrast, main incisions are larger and thus easier to find, facilitating emerging bridges to be bluntly dissected.

Of course, standardizing incisions allows for greater precision, enhancing predictability and minimizing deviations from the intended incision shape. This is essential to avoid corneal refractive errors and optimize refractive outcomes [11,12]. As cataract surgery increasingly evolves into a refractive procedure.

With high patient expectations, this precision is important not only for premium IOLs but also for monofocal IOLs.

When performing FLACS, the automated detection of tissue structures is important for the preoperative planning of CCIs. In this context, limbus detection is critical but can be impaired by limbal vessels and an arcus lipoides [13]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the overall patency of paracenteses in FLACS while analysing the impact of limbus detection quality, arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels on the resulting incision patency.

Study design and patients

This prospective clinical unmasked single-centre study included 159 eyes, 81 right and 78 left, from 123 patients, 80 males and 43 females, who underwent FLACS with the FEMTO LDV Z8 (Ziemer Ophthalmic Systems, Port, Switzerland). Mean age was 70.7 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 8.2 years.

Inclusion criteria were a cataract with indicated surgery, patient age over 18 years, consent to the femtosecond laser-assisted procedure, and the legal, mental, and psychological ability to give this consent. Exclusion criteria were corneal dystrophy, limbal stem-cell insufficiency, status post keratoplasty, traumatic corneal scars, or congenital glaucoma, as well as pregnancy and nursing. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients after the nature of the study had been explained. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (175/14, 15.10.2015) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery

After disinfection, anesthesia, and eyelid retractor placement, the suction ring was positioned first, followed by filling the interface with balanced salt solution before docking the laser head. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed, followed by capsulotomy, core fragmentation, and CCIs. After undocking of the laser head, the incisions were opened using a special FLACS cannula (FLACS Cannula 25G, Beaver-Visitec International, UK). Ophthalmic viscosurgical device material was introduced in the anterior chamber, and the capsule was removed with forceps to create a free-floating situation. Hydrodissection, hydrodelineation, and phacoemulsification of the nucleus and epinucleus in the chop technique were performed, followed by aspiration of cortical debris and posterior capsule polishing. The folded intraocular lens (IOL) was implanted endocapsularly and centered before aspiration of the ophthalmic viscosurgical device material. A standard regimen consisting of 1 mg dexamethasone and 1 mg/0.1 ml cefuroxime was administered intracamerally. Paracenteses were closed by freezing.

Femtosecond laser settings

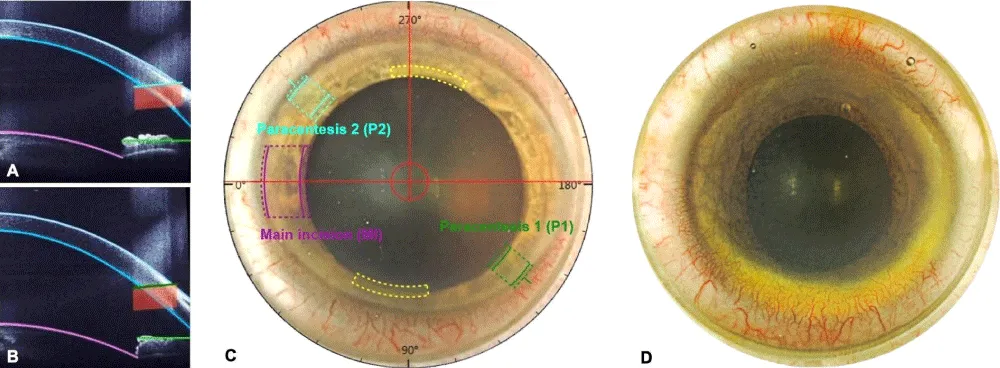

The following laser settings were used to ensure standardization: Width of the paracenteses (1 and 2 = 1.1 mm), distance from the limbus to the paracenteses (1 and 2 = 0.1 mm), entry angle of the corneal incisions (right eye: P1 = 35°/45°, P2 = 140°/135°; left eye: P1 = 135°/15°, P2 = 315°/140°, where P = paracentesis). The automated presetting of the paracenteses is displayed in Figures 1A, 1B, and 1C. The surgeon reserved the right to change the presetting for corneal incisions to a more central or peripheral position when patency was assumed to improve. The axis of the incisions was never changed.

Scoring

The surgeon documented all intraoperative findings, including the patency of the incisions. To evaluate the intraoperative patency of the incisions (labeled “yes”, “no”, or “with bridges”), the surgeon used a special cannula for FLACS (FLACS Cannula 25G, Beaver-Visitec International, UK). If an incision could be directly opened without resistance, it was considered patent (“yes”). If an incision could be opened but with resistance, it qualified as a bridge (“with bridges”). Tight was tight (“no”). Altogether, the influence of the surgeon’s subjective impression is considered marginal.

As described in our previously published paper [13], automated limbus detection, the extension of the arcus lipoides, and the occurrence of limbal vessels were evaluated using a self-designed grading scheme (Table 1 and Figure 1D).

| Table 1: Grading scheme for the evaluation of limbus detection, arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels (h = clock hours). | ||||

| Quality of limbus detection | N/A | good | moderate | poor |

| Arcus lipoides | none | low | mild | severe |

| Limbal vessels | none | 0–1 h | 1–2 h | 2–3 h |

Figure 1: Eye photograph (A) and anterior segment optical coherence tomography imaging (B and C) with automated pre-setting of the clear corneal incisions using the FEMTO LDV Z8. The paracentesis 1 is marked in green at 135°, and paracentesis 2 is marked in light blue at 315°. The purple and yellow markings show the location of the main and arcuate incisions. Grading example (D): The inferior quadrant (down) showed a severe arcus lipoides with vascularization extending over 3 hours and poor limbus detection, the temporal quadrant (left) showed a mild arcus lipoides with vascularization extending over 2 hours and moderate limbus detection, the superior quadrant (up) showed a low arcus lipoides with vascularization extending over 3 hours and moderate limbus detection, and the nasal quadrant (right) showed a severe arcus lipoides with vascularization extending over 1 hour and poor limbus detection.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the analysis software “R” (version 3.6.3). Data is displayed using means, standard deviations (SDs), or percentages, as appropriate. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. p values (p) were two-tailed and considered statistically significant when < 0.05. The paracenteses 1 and 2 were summarized for statistical analysis.

A total of 29 of the 159 eyes were excluded from the statistical analysis owing to incomplete data recording. Thus, 130 eyes, 72 right and 58 left, from 108 patients, 70 males, and 38 females, with a mean age of 70.5 ± 7.8, resulting in 259 paracenteses were evaluated. No cases of postoperative endophthalmitis were recorded.

Side-port incision patency

The paracenteses were patent in 257 of 259 cases (i.e., 99.2%). In 2.7% of these cases, intrastromal tissue bridges were observed, all of which were separable through blunt manipulation. Only 0.8% of cases required a blade to open the paracentesis. Shifting the programmed side-port incision manually to the periphery or center had no significant impact on patency (p = 0.60, Chi-Square). In addition, no difference in patency rates was found between the right and left eyes (p > 0.99, Chi-Square), nor among the analyzed quadrants (p = 0.36, Chi-Square).

Limbus detection

The quality of limbus detection was rated as “poor” in 38.5% - 55.4% of cases, with the lowest percentage observed in the superior quadrant and the highest in the nasal quadrant (Table 2). A “moderate” rating was assigned in 14.6% - 23.1% of cases, while a “good” rating was recorded in 26.2% - 43.1% of cases, with the lowest percentage in the nasal quadrant and the highest in the inferior quadrant (Table 2). These variations resulted in a significant difference among the four quadrants (p = 0.047, Chi-Square). However, pairwise comparisons did not reveal any significant differences (Chi-Square).

| Table 2: Quality of limbus detection for each quadrant. | ||||

| Limbus detection | Superior quadrant |

Temporal quadrant |

Inferior quadrant |

Nasal quadrant |

| Poor | 50 (38.5%) | 60 (46.2%) | 55 (42.3%) | 72 (55.4%) |

| Moderate | 30 (23.1%) | 26 (20.0%) | 19 (14.6%) | 24 (18.5%) |

| Good | 50 (38.5%) | 44 (33.8%) | 56 (43.1%) | 34 (26.2%) |

Arcus lipoides

An arcus lipoides was detected in 67% of cases in the superior quadrant, 44.6% in the temporal quadrant, 26.2% in the inferior quadrant, and 53% in the nasal quadrant (Table 3). These differences were significant among all four quadrants (p < 0.001, Chi-Square). However, when present, the arcus lipoides was most commonly rated as “low” in severity, ranging from 13.8% to 33.1% of cases (Table 3). Pairwise comparisons between quadrants, considering both the presence and graded severity of the arcus lipoides, were largely significant (p < 0.05, Chi-Square), with the exception of the comparison between the temporal and nasal quadrants.

| Table 3: Occurrence of arcus lipoides in each quadrant. | ||||

| Arcus lipoides | Superior quadrant |

Temporal quadrant |

Inferior quadrant |

Nasal quadrant |

| none | 42 (32.3%) | 72 (55.4%) | 96 (73.8%) | 61 (46.9%) |

| low | 43 (33.1%) | 38 (29.2%) | 18 (13.8%) | 41 (31.5%) |

| mild | 27 (20.8%) | 7 (5.4%) | 6 (4.6%) | 13 (10.0%) |

| severe | 18 (13.8%) | 13 (10.0%) | 10 (7.69%) | 15 (11.5%) |

Limbal vessels

The distribution of limbal vessels varied significantly across the four quadrants (p < 0.001, Chi-Square). In the temporal and nasal quadrants, the majority of eyes had no detectable vessels (69.2% and 62.3%, respectively; Table 4). In contrast, limbal vessels were observed in 84.6% of cases in the superior quadrant and 65.4% in the inferior quadrant (Table 4). Notably, in the superior quadrant, vessels extended across 2–3 clock hours in 42.3% of cases (Table 4). Pairwise comparisons between the superior or inferior quadrant and the remaining quadrants were all significant (p < 0.002, Chi-Square).

| Table 4: Presence of limbal vessels in each quadrant. | ||||

| Limbal vessels | Superior quadrant |

Temporal quadrant |

Inferior quadrant |

Nasal quadrant |

| none | 20 (15.4%) | 90 (69.2%) | 45 (34.6%) | 81 (62.3%) |

| 0–1 clock hour | 18 (13.8%) | 31 (23.8%) | 19 (14.6%) | 40 (30.8%) |

| 1–2 clock hours | 37 (28.5%) | 8 (6.15%) | 33 (25.4%) | 9 (6.9%) |

| 2–3 clock-hours | 55 (42.3%) | 1 (0.77%) | 33 (25.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Influence of limbus detection, arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels on the patency: Quality of the limbus detection was rated as “good” in both cases where paracentesis patency was not achieved (Table 5). Tissue bridges were observed in cases where limbus detection was rated as “poor” in five instances and “moderate” in two. However, no significant association was found between limbus detection quality and either paracentesis patency or the occurrence of intrastromal bridges (Table 5).

| Table 5: Impact of limbal detection, the arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels on the patency of the paracenteses. n = total number of patients. | ||||

| Patency | Yes | No | Bridges | |

| Total | n = 259 | n = 250 | n = 2 | n = 7 |

| Limbus detection | poor | 126 (96.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (3.8%) |

| moderate | 45 (95.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.3%) | |

| good | 79 (97.5%) | 2 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Arcus lipoides | none | 122 (96.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.2%) |

| low | 73 (96.1%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| mild | 27 (93.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.9%) | |

| severe | 28 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Limbal vessels | none | 151 (98.1%) | 1 (0.65%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| 0–1 hour | 67 (93.1%) | 1 (1.4%) | 4 (5.5%) | |

| 1–2 hours | 25 (96.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | |

| 2–3 hours | 7 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

The arcus lipoides was rated as “low” in both cases where patency was not obtained (Table 5). Conversely, all eyes with an arcus lipoides rated as “severe” had patent paracenteses. Among the seven cases with intrastromal bridges, the arcus lipoides was rated as “low” in one case and “mild” in two cases, while it was absent in the remaining four cases. No significant association was found between the presence or severity of an arcus lipoides and either paracentesis patency or the occurrence of intrastromal bridges (p > 0.05, Chi-Square; Table 5).

Limbal vessels were absent in one of the two cases where paracentesis patency was not achieved, while in the other, the vessels extended over 0–1 clock hours (Table 5). Among the seven cases with intrastromal bridges, limbal vessels were absent in two cases, extended 0–1 clock hours in four cases, and 1–2 clock hours in one case. Ultimately, no significant association was found between the presence or extent of limbal vessels and either paracentesis patency or the occurrence of intrastromal bridges (Table 5).

In modern cataract surgery, CCIs are now largely preferred over scleral incisions [14]. The primary advantages of CCIs include faster visual recovery, shorter procedure times, sutureless wounds, and a reduced risk of bleeding. However, the technique also presents certain disadvantages, such as higher rates of wound leakage, postoperative endophthalmitis, and surgical-induced astigmatism (SIA), as well as an increased risk of endothelial cell loss [14]. Several studies have explored various CCI techniques in an effort to identify those with the fewest disadvantages. One key factor in minimizing complications is ensuring proper sealing of the incision, which helps reduce the risk of postoperative hypotony and wound leakage, both of which are significant risk factors for developing postoperative endophthalmitis [14,15]. Additionally, the localization, size, and architecture of the incision are important for the success of CCIs. Grewal and Basti compared the morphological characteristics of CCIs created with either a femtosecond laser or a keratome using anterior-segment OCT [16]. They found that femtosecond laser-generated CCIs exhibited significantly less endothelial gaping and misalignment, Descemet membrane detachment, and posterior wound retraction compared to keratome-created CCIs. Furthermore, femtosecond laser-generated CCI were within 10% of the intended length, depth, and angle, demonstrating high accuracy and reproducibility [16]. These findings align with those from Ferreira, et al. who reported superior reproducibility of femtosecond laser-generated CCIs in terms of SIA and wound architecture [17].

Current research suggests that corneal incisions should be created as close to the limbus as possible for optimal outcomes [18]. Additionally, multiple studies indicate that incisions smaller than 3 mm provide greater stability, reduce wound leakage, and have a lower impact on SIA compared to larger incisions [19-24]. In this study, all incisions were precisely positioned 0.1 mm from the limbus, with paracenteses measuring 1.1 mm in width. Since wound leakage and SIA were not the primary focus of this study, they were not specifically analyzed. However, based on existing literature, it can be reasonably assumed that the 1.1 mm paracenteses would exhibit minimal wound leakage and a negligible impact on SIA [9,16,17].

The automated detection of tissue structures plays a crucial role in FLACS, particularly for preoperative planning, including capsulotomy, lens fragmentation, and corneal incisions [25]. In a previous study, we showed that neither limbus detection quality nor the presence of an arcus lipoides significantly affected incision patency. However, a pronounced presence of limbal vessels was associated with a lower patency rate. Despite this, the overall patency rate of the main incisions remained high at 97% [13].

While several studies highlight the advantages of automated cutting systems in FLACS for CCIs, most cataract surgeons using lasers still perform side-port incisions manually with a keratome [10]. However, our results indicate an excellent patency rate of over 99% when using a blunt cannula to open the paracentesis pre-cut by the FEMTO LDV Z8 laser. Tissue bridges were observed in fewer than 3% of these cases. Although limbus detection was rated as “poor” in approximately 40% - 50% of cases across all quadrants, it did not significantly impact patency. Similarly, neither arcus lipoides nor limbal vessels had a significant effect on the patency rate.

Further studies with larger case numbers will be necessary to better identify factors contributing to non-patent paracenteses. Given the extremely high patency rate achieved, the number of non-patent cases remains very small, making further analysis herein challenging.

Comparing these results with manual incisions is difficult. While manual incisions are always open, they exhibit greater variability in size, length, and positioning. The key advantage of FLACS is its ability to achieve near-perfect precision and reproducibility. Importantly, the relatively poor limbus detection in some cases did not compromise patency outcomes.

Notably, no cases of postoperative endophthalmitis were reported in this study. In a previous study, we did not observe a decrease in endothelial cell density in a similar cohort [26].

The high precision and reproducibility of FLACS incisions could play a crucial role in surgical training and broader adoption. For less experienced surgeons, the laser offers the advantage of creating incisions with standardized depth, width, and positioning, leading to more consistent outcomes. This increased consistency could enhance the integration of FLACS into training programs and, over time, promote its wider adoption.

Our findings suggest that automated paracentesis should be considered a standard option in the FLACS protocol, particularly in institutions that already use FLACS for the main incision but continue to perform paracentesis manually. Despite the high patency rate observed, several questions remain for future studies, such as whether the position or architecture of the incision influences long-term refractive outcomes and whether adjustments to laser energy or incision guidance could further improve patency rates or reduce intrastromal tissue bridges.

Side-port incisions or paracenteses in cataract surgery remain underrepresented in the literature, particularly in the context of FLACS, limiting the comparability and reproducibility of data. A recent study by Lin, et al. compared two femtosecond laser systems for cataract surgery, the LenSx and the FEMTO LDV Z8, and, to our knowledge, it is the only study aside from ours to analyze the patency of side-port incisions in FLACS [27]. Their findings demonstrated a high overall patency rate (~90%), though lower than what we observed. Notably, Lin, et al. did not examine the impact of limbal vessels, arcus lipoides, or limbus detection quality on incision patency [27]. They did, however, suggest that incisions placed closer to the limbus might be more difficult to open due to increased corneal thickness and reduced transparency toward the periphery [27]. This contrasts with our study, where paracenteses were created just 0.1 mm from the limbus, and manually adjusting the side-port incision position had no statistically significant effect on patency.

Our results provide strong evidence to address concerns regarding automated side-port incision creation in FLACS. With a patency rate exceeding 99%, our study demonstrates that FLACS side-port incisions with the FEMTO LDV Z8 are highly performant. Moreover, neither poor limbus detection nor the presence of limbal vessels nor an arcus lipoides significantly affected paracentesis patency.

These results provide direct evidence supporting the high clinical value of the automated presetting and femtosecond laser cutting system for paracenteses as a viable alternative to manual incision techniques.

The authors wish to thank Rudolf Siegel for excellent support during statistical analysis.

Ethics approval statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ärztekammer des Saarlandes (protocol code 175/14, date of approval 15.10.2015).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.- Binder PS. Femtosecond applications for anterior segment surgery. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36:282-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/icl.0b013e3181ee2d11

- Dick B, Gerste RD, Schultz T. Femtosecond laser surgery in ophthalmology. Thieme; 2018. Available from: https://www.thieme-connect.de/products/ebooks/book/10.1055/b-005-143342

- Gray B, Binder PS, Huang LC, Hill J, Salvador-Silva M, Gwon A. Penetrating and intrastromal corneal arcuate incisions in rabbit and human cadaver eyes: manual diamond blade and femtosecond laser-created incisions. Eye Contact Lens. 2016;42:267-73. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/icl.0000000000000204

- Mastropasqua L, Toto L, Mastropasqua A, Vecchiarino L, Mastropasqua R, Pedrotti E. Femtosecond laser versus manual clear corneal incision in cataract surgery. J Refract Surg. 2014;30:27-33. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597x-20131217-03

- Lee YW, Cho KS, Hyon JY, Han SB. Application of femtosecond laser in challenging cataract cases. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2023;12:477-85. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/apo.0000000000000627

- Naranjo-Tackman R. How a femtosecond laser increases safety and precision in cataract surgery? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:53-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/icu.0b013e3283415026

- Soong HK, Malta JB. Femtosecond lasers in ophthalmology. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:189-97.e2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2008.08.026

- Gavris MM, Belicioiu R, Olteanu I, Horge I. The advantages of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2015;59:38-42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27373114/

- Hill JE, Binder PS, Huang LC. Leak-free clear corneal incisions in human cadaver tissue: femtosecond laser-created multiplanar incisions. Eye Contact Lens. 2017;43:257-61. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/icl.0000000000000262

- Song C, Baharozian CJ, Hatch KM, Talamo JH. Assessment of surgeon experience with femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:1373-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/opth.s171743

- Anders N, Pham DT, Liekfeld A, Pham DT, Wollensak J. [Factors modifying postoperative astigmatism after no-stitch cataract surgery]. Ophthalmologe. 1997;94:6-11.

- Pham DT, Wollensak J. ["No-stitch" cataract surgery as a routine procedure. Technique and experiences]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1992;200:639-43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1045848

- Boden KT, Schlosser R, Reipen L, Seitz B, Januschowski K, Szurman P. The impact of limbus detection, arcus lipoides, and limbal vessels on the primary patency of clear cornea incisions in femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99:e943-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14705

- Al Mahmood AM, Al-Swailem SA, Behrens A. Clear corneal incision in cataract surgery. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21:25-31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-9233.124084

- Wallin T, Parker J, Jin Y, Kefalopoulos G, Olson RJ. Cohort study of 27 cases of endophthalmitis at a single institution. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:735-41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.10.057

- Grewal DS, Basti S. Comparison of morphologic features of clear corneal incisions created with a femtosecond laser or a keratome. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40:521-30. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.11.028

- Ferreira TB, Ribeiro FJ, Pinheiro J, Ribeiro P, O'Neill JG. Comparison of surgically induced astigmatism and morphologic features resulting from femtosecond laser and manual clear corneal incisions for cataract surgery. J Refract Surg. 2018;34:322-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597x-20180301-01

- Wang L, Zhao L, Yang X, Zhang Y, Liao D, Wang J. Comparison of outcomes after phacoemulsification with two different corneal incision distances anterior to the limbus. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:1760742. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1760742

- Ernest PH, Lavery KT, Kiessling LA. Relative strength of scleral, corneal, and clear corneal incisions constructed in cadaver eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1994;20:626-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80651-7

- Febbraro JL, Wang L, Borasio E, Richiardi L, Khan HN, Saad A, et al. Astigmatic equivalence of 2.2-mm and 1.8-mm superior clear corneal cataract incision. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253:261-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-014-2854-5

- Hayashi K, Sato T, Yoshida M, Yoshimura K. Corneal shape changes of the total and posterior cornea after temporal versus nasal clear corneal incision cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103:181-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311710

- Masket S, Belani S. Proper wound construction to prevent short-term ocular hypotony after clear corneal incision cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:383-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.11.006

- Nikose AS, Saha D, Laddha PM, Patil M. Surgically induced astigmatism after phacoemulsification by temporal clear corneal and superior clear corneal approach: a comparison. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:65-70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/opth.s149709

- Yu YB, Zhu YN, Wang W, Zhang YD, Yu YH, Yao K. A comparable study of clinical and optical outcomes after 1.8, 2.0 mm microcoaxial and 3.0 mm coaxial cataract surgery. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9:399-405. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2016.03.13

- Sun H, Fritz A, Dröge G, Neuhann T, Bille JF. Femtosecond-laser-assisted cataract surgery (FLACS). In: Bille JF, editor. High resolution imaging in microscopy and ophthalmology: new frontiers in biomedical optics [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2019. Chapter 14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16638-0_14

- Mariacher S, Ebner M, Seuthe AM, Januschowski K, Ivanescu C, Opitz N, et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery: first clinical results with special regard to central corneal thickness, endothelial cell count, and aqueous flare levels. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42:1151-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.06.024

- Lin HY, Chuang YJ, Lin PJ. Surgical outcomes with high and low pulse energy femtosecond laser systems for cataract surgery. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9525. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89046-1